The finance industry is facing large disruption, and it isn't coming from within. The industry needs to consider the reasons they will be disrupted, be prepared for radical new business models, and look to outsiders who aren't afraid to break the status quo in order to understand why the real disruption is not the incremental tech innovation that they are so enamored with.

Most Disruption Isn't

Disruptive innovation is an incredibly practical and reliable theory about competition, which describes how new market entrants consistently win against established market leaders when a clearly identifiable set of conditions are present. Its usefulness as a business tool is being threatened by poor understanding, widespread misuse of the term, and often deliberate exaggeration by marketers and media pundits who don't appreciate the damage they are doing.

Is Febreze Disruptive? It Might Depend What Job You Hire it For.

I often start by reminding clients and prospects -- anyone who will listen -- that an innovative technology is a nice thing to have, and can certainly enable market disruption if it uniquely enables a large sustainable cost advantage, or a new way of doing things that is easier or more convenient. But technology is neither necessary, nor sufficient for disruption to occur.

Disruptive innovation is not about technology

Netflix was a good example in their early days. Yes, you placed orders for movies through a website, but there was nothing about the website that was novel or necessary in order to disrupt Blockbuster. In fact, they were considered a tech play because of the website, but there was nothing about technology that made Netflix successful (something they would have done well to remember when they tried to force an ill-advised price change on customers last year to combine streaming video and mailed DVDs). When Blockbuster added their own website and copied much of the mechanics of Netflix's ordering, it made no difference to their survival and did not enable them to prevent being disrupted.

Netflix's disruptive innovation was driven entirely by their business model. Apparently inferior to Blockbuster in the lack of physical presence to visit and browse movies and take something home to watch NOW (at least that's how Blockbuster positioned themselves against Netflix), they identified unmet and underserved market needs and created a new business model to serve them. By sending DVDs mail order from a central location, Netflix eliminated the huge cost of stores, and having inventory where it wasn't needed, and in the process enabled:

- limitless catalog

- convenience of not having to make a trip to the store either to pick up or return videos

- low cost for high volume renters aka the best customers (flat subscription pricing rather than per video)

and removed friction in the rental process:

- no late fees -- the number one complaint against Blockbuster and traditional video rental models

- frustration when a desired title wasn't on the shelf

Dramatically lower costs could be passed on to consumers (and sustainable cost advantage is one of the key drivers of disruption), enabling rapid growth, and strong word of mouth helped Netflix avoid big marketing costs to grow.

What does this have to do with Febreze? Well, I started with Netflix because it is an example commonly misunderstood to be a technology-based disruptive innovation, when it really has nothing at all to do with technology, but is entirely about the process, the business model and the marketing. It's a company that most of us are familiar with, especially after its recent missteps, and it helps us make the leap to talking about a disruptive innovation that doesn't have any "tech" in it at all.

How the heck is an air freshener in a crowded marketplace an example of disruptive innovation?

Febreze is fascinating, because it started its life doing everything wrong, the way most "big company" new products are introduced to market. It was a product designed to be sprayed on draperies that reeked of cigarette smoke, a smelly sofa that was frequently inhabited by a wet family dog, or a room where cats had done their thing on the floor. It's purpose was to neutralize the odor.

The problem was, this was a made-in-the-boardroom problem. Although it seems reasonable to imagine that people are embarrassed and repulsed by these smells and would want to get rid of them, in the real world, the people who most needed to fix this problem didn't believe that they had a problem to fix. In the real world, people build up tolerances to smells the more they are exposed to them, and may even associate that "wet dog" smell with positive feelings. So, while any visitor to such a home might be hit in the face with detestable odors and wonder how people could live that way, the person who lives there has masked the smells in their mind and has no idea that their house smells like smoke, or like cat pee. And, even if they smell it a little bit, they certainly don't perceive their house to be unclean and in need of yet another kind of air freshener product.

So, when P&G launched Febreze as an odor-killing unscented spray in the mid-90s with ads targeting the homeowner's love for their pets, but hate for their smell, there was no resonance in the market with this messaging (might they have done better to target visiting friends instead?), and it was a complete dud in the market, with sales falling each month, rather than growing.

This scenario is laid out in a New York Times article (see pages 4 and 5 for the bit about Febreze) that details the work of behavioral researchers in understanding habits to influence purchasing decisions. The company was perplexed and sent researchers out to the field to try to understand what was happening with happy users of Febreze who were using lots of it, and what was different about them. Did they have more sensitive noses? Were they more anal about cleaning? Were they more socially embarrassed about the smells when visitors came over?

Febreze became an innovative market disruptor, almost by accident

It turned out that there were some avid users who had built spraying into their regular cleaning habits as a reward for finishing, so when the bedroom was finished being cleaned and tidied, a quick spray of Febreze on the comforter was the icing on the cake. When the laundry was clean, a spray of Febreze confirmed it. When the living room was cleaned and the sofa vacuumed off, Febreze was the finishing ritual. It wasn't that they perceived their homes to be dirty or in need of de-smelling, but that the spray at the end was a finishing detail to signal completion and get that little endorphin high that comes with completing something.

The happy ending is that P&G discovered this counter-intuitive behavior, and built this notion into their marketing. Sales exploded, to the point that it is today a best-selling $1B franchise. The now familiar ad template shows a giddy, self-gratified housewife who has finished the cleaning, gives it a shot of Febreze and closes her eyes to breathe in the warm fuzzy feelings. Or, more prosaicly, a quick spray when finished the task was the reward for finishing - the idea being to associate the product with habit formation and the good feeling of being done with the work and knowing that things were clean. In other words, rather than promoting it as a cleaning product, they are promoting it as something you should do after cleaning was complete.

So, the NYT article is about how statisticians and behaviorists are decoding habits and using them to sell to us, and the Febreze story is just a small piece of it, but it got me to thinking. What's interesting is that the original launch of Febreze was supported by conventional wisdom and conventional marketing. I'm sure they did research that confirmed everyone would like their homes to smell cleaner (a common symptom of bad market research is "confirmation bias", where people selectively remember things that confirm what they already believe to be true, or in this case, remember how much they dislike the smell in everyone else's home even when they don't recognize it in their own). Febreze would have been just another incremental and sustaining cleaning innovation, but for the discovery of this anomalous behavior of a few avid users. It may even have been cancelled for lack of sales had behavioral researchers not discovered the pattern of women using it when finished cleaning a room, rather than as a way to deodorize pet smells.

But hidden in the research story is that Febreze's ultimate success points to some critical factors that all "new market" disruptive innovations exhibit. Most notably:

job to be done. Early on, marketers positioned Febreze as an air freshener because they didn't understand the "job" that consumers were hiring it to do. It turns out that people didn't believe they had a smell problem. But, a quick spray at the end of cleaning a room created a habit-forming ritual that said "I'm done. This is clean and fresh and I can move on to the next room." A reward, and a signal of being clean, rather than a coverup of something shameful. Had the real job not been discovered, Febreze likely would have failed in the market as one of thousands of similar cleaning product innovations. By precisely targeting the job that the consumer identified with, they created positioning that is virtually impossible to dislodge them from. (Download this classic article which describes why identifying the job to be done is so important.)

target non-consumption. There were a small number of people who felt they needed a bandaid solution to mask disgusting smells. However, most people didn't recognize or agree that their house smelled bad, but did see a quick spray as a finishing touch -- almost like putting some sparkle on their lip gloss. By targeting the larger market of people who did not think their houses stunk and needed air fresheners as masking agents, but who did clean their houses, Febreze was able to identify a unique niche to dominate and grow from (now, people do buy Febreze as a quick fix to mask unpleasant odors, but that came later).

serve an unmet need. There was clearly an unmet need to signal "I'm done" and have a little celebration before moving to the next room. I suspect we all have this little celebration, whether we use Febreze or not, we step back and admire our work, smell the air. Febreze sprinkles the fairy dust that completes the job (that's how the ads seem to portray it). Originally unscented (because it was to mask odors, not replace them), Febreze now comes in many perfumed scents to leave behind the smell of "being done".

identify a new market. The new market for a deodorizing spray was people who viewed it as a finishing tool for cleaning. The people who it was originally designed for (those with smelly houses) didn't think they needed it, so the only way to sell it was to identify a new (adjacent) market where there was an unmet need.

Startups who are designing groundbreaking technologies that they believe are "disruptive" do well to remember these lessons. Disruption is a theory about marketing, not about product development or technology. To disrupt a market, you must be able to articulate a "job to be done" for which your target audience believes there is no better solution. You must meet an unmet or under-served need -- it's easier to sell to people who aren't part of the existing market (non-consumers who have opted out, and indicated that no available solution either satisfies the "job to be done" or is priced affordably), than to compete against incumbent solutions claiming to be better. And, you either need to be a "low-end" disruption (one which is targeted at the least demanding market segments based on pricing and sustainable cost advantage) or a "new market" disruption (create a market where none existed before).

Marketing and business strategy drive disruption

None of these characteristics have anything to do with building technology, but everything to do with appropriate segmentation, product positioning, messaging, and the compelling reasons why I would select your solution over all other available alternatives (which aren't necessarily products in the same "category"). Febreze ended up being a disruptive innovation because it succeeded (albeit after the fact) in marketing strategy, not because of how the product was designed.

Your thoughts?

Is Disruptive Innovation important to your business strategy? Download a free copy of the eBook 'Disruptive Confusion Unraveled' to learn:

- the 6 most common misconceptions about disruptive innovation

- how disruption creates growth

- what it means to be disruptive and why the definitions matter

- how to predict market disruption

- how to measure the market value of being disruptive

The 6 Most Common Misconceptions About Disruptive Innovation

In the nearly 15 years since The Innovator's Dilemma was published, the notion of disruptive innovation has grown in awareness immensely, particularly among tech startups, venture capitalists and angel investors.

It has become the holy grail for investors and entrepreneurs, with many funds targeting disruption exclusively. Yet, as strong as this meme has become, it is also one of the most widely misused and misunderstood terms among those same groups.

Misuse, Overuse, Confused Use

We can speculate about the reasons why. Certainly the word 'disruptive' is at once a powerful and suggestive descriptor, and simultaneously an instrument of misdirection. Disruption had a (strong) meaning before Christensen appended it to Innovation to label his theory (that's why he used it), and many simply imbue the phrase "disruptive innovation" with their personal interpretation of what it means to be disruptive. Or, they focus on the innovation part of the term, and think that means it's all about technology (it isn't).

More importantly, I think, is that the language Christensen used to write The Innovator's Dilemma is highly academic, sometimes deliberately ambiguous, often speculative, and extremely dense. When these attributes are combined, it makes for very difficult reading that is hard to make sense of even for dedicated practitioners and students of the theory. Then to compensate, Christensen himself often tries to over-simplify the theory to summarize it, and people take the simplistic descriptions as a complete rendering, repeating them as axiomatic.

On top of all that, the theory has been refined over time, but most people have read only the original book, if they've read anything at all. It's a a perfect storm prescription for confusion and misuse.

Not Just Another Square on the Buzzword Bingo Card

The result is that there are dozens of people preaching the gospel of disruption, many if not most with their own (commercial) agenda, and it is rare to find any two in agreement. Well over 95% of headlines and articles written about disruption are blatantly wrong or misguided, or metaphorical at best. And, many pundits and writers have taken a great deal of liberty and license in inventing their own definitions, or expressing what they think the theory says rather than the model it actually describes. Thus, we have tremendous misinformation, misunderstanding, and strong misconceptions about what the theory is, which is a shame because it is possibly the most important economic theory of the past 50 years.

Getting Disruption Right Matters

The problem with all the misinformation, fuzziness about what it is and isn't, and even deliberate misrepresentation is that if businesses don't understand what disruptive innovation really is, and what the opportunities and threats are, then the theory can't be applied. And, the whole point of identifying this phenomenon and describing how it works is to improve: to not be blindsided when new disruptions are on the horizon, to capitalize on massive growth opportunities, and place intelligent bets on the future by making wise investments.

Getting it wrong is like the old saw "if you don't know where you're going, then any direction will get you there". It's no different than if Christensen had never developed the theory in the first place.

Clarity About Disruption

In a newly published eBook designed to bring clarity and simplicity to the discussion and outline the business significance of disruption innovation from financial, growth, investing and risk perspectives, Innovative Disruption's CEO, Paul Paetz, describes the 6 most common misconceptions about market disruption. They include:

- All innovation is disruptive by definition

- Innovation has to be breakthrough to be disruptive

- Disruption only applies to technology

- "Disruptive" is just a marketing adjective companies use to imply that their product is more advanced

- Disruptive innovation is a meaningless buzz phrase

- All innovation is overrated, and disruptive innovation isn’t any better or different

Of course, all these notions are wrong.

Get your copy of 'Disruptive Confusion Unraveled' to learn:

- why there are so many misconceptions

- the strategic importance to entrepreneurial innovators and investors

- what it means to be disruptive and why the definitions matter

- how to recognize and predict disruption and measure its value

Note to American Idol: Fight Disruption with "Jobs to Be Done" Focus

My old guilty pleasure, American Idol, ended a few weeks ago, and I got to reflecting on the dynamics of the show itself and whether an article I wrote just before last year's finale would prove to be prophetic on review.

Last year's analysis discussed how AI was being disrupted, and whether the producers were either ignoring the problem, or didn't get it. In my review, I suggested some prescriptive changes that they needed to undertake to avoid an otherwise inevitable fate.

So, how did I do?

Last Year's Analysis and Predictions, Issues and Opportunities

- American Idol rules the roost; as #1 rated show, it has become complacent and resistant to necessary change and highly susceptible to disruption

- Any changes have become largely cosmetic (incremental "sustaining" innovations), and they've "overshot" the audience needs on the "slickness dimension" and no longer approximate an "authentic" experience

- The reality that creates ratings for Fox is that only a couple of the top 12 are actually good enough to have a chance at winning. The rest are there to become the train wrecks we want to vote off, to sass back at Simon, to sing gloriously out of tune and make us laugh, to impress with their self-absorption or self-delusion or just plain wacky personalities, to do whatever they do with Paula, and most of all, to give the audience time to get to know the eventual winner and build a following to buy their records.

- The ruse being perpetrated is that the show is really a singing competition, when in reality the producers have constructed a promotional stage which sells lots of advertising (because of the entertainment value in seeing train wrecks get voted off the island) and a vehicle for selling pop records, crafted in the form of a quasi-reality show

- A large minority of the audience has seen the wizard behind the curtains and tired of the deception, and using the power of the web, started to turn the tables on the show's producers, exposing the sham and actively working as a block to "Vote for the Worst", keeping the train wrecks going as long as possible at the expense of singers that the judges and producers actually wanted to "win". Last year, this resulted in the best singer (by any objective measure) being voted off early and two mediocre performers making it to the finale. The resulting winner's album was awful, and sold miserably (opening week sales for Jordyn Sparks first AI record were less than 1/2 same stat for Fantasia, the previous worst-selling AI winner, and only about 40% of the same stat for Taylor Hicks, who was generally considered a bomb and was dropped by his label).

- The voting system that Idol uses is suspect to begin with. By asking the audience to vote for their favorites, and as many times as they want, they have created a system which generates revenue but can't reliably identify either the best singer or the audience favorite(s). Even superior voting systems (audience votes for the worst and the person getting the most negatives is eliminated, one vote per person, one ballet with yays and nays for all contestants tabulated, it is open to manipulation, but the way it is, the best singers and performers are routinely voted off several weeks too early.

- Because of the above, the grand prize of a recording contract has become meaningless, and even a bit of an albatross. The contestants voted off early routinely get recording contracts and outsell the winners, because they a) can sing better, b) have more control over their albums (AI doesn't dictate what they can sing or how it gets produced), and c) therefore better songs, or at least songs they are better suited to sing, get on their albums.

The Two Davids: David Cook and David Archuleta

Note that to try to deal with the last point, the judges practically fell over themselves this season to tell the voting audience as bluntly as possible who they thought needed to go and who should stay in an apparent effort to ensure that one of their favored singers actually won this time. They became so transparent about it, that Paula got caught offering judgment about a song that hadn't yet been sung, casting the wizard's curtain wide open.

Our conclusion: the above factors are causing audience disenchantment, and eating into viewership. The cynical business model that AI uses to milk the show for maximum revenue was easily disrupted by a little website exposing the underlying deceit.

The Results Are In

So, are these predicted results actually happening? If so, how are they manifesting?

- Viewership in 2008 was down an astounding 7% from 2007

- In a year where the two stars were considered "hot" guys, the primary viewing audience of women aged 18 to 34 was down by 18%

- The median age continues to skew ever upward, from mid 30s a few years ago, to 42 today. Hardly the prime music buying age group.

- The over 50 age group has increased in viewership.

All this suggests increasing irrelevance to the trendsetting youth audience, boredom among core fans, and disenchantment and disenfranchisement from the process. Typically when this sort of thing begins, it is irreversible because by the time executives acknowledge it is a serious problem (whether the product is a tv show, a newspaper, or a me-too generic cell phone, it's too late to make the major changes necessary to right the ship.

Will American Idol will take my advice? There's no doubt they have to do something and we're highly likely to see some changes next year, but the question is, how will they diagnose what's going on, and therefore come up with appropriate solutions. (It's at this point that I should helpfully point out that if they want to get the skinny on how to counter this disruption before it kills the show, I'm available as a consultant.) Here's a little free advice:

- The dynamics are old, and some highly visible changes are necessary. First to get the shake up should be the judging crew. Only Simon is core to the program -- it's time for Paula and Randy to go. Besides, the show needs more authenticity, and you can always count on Simon to say what he thinks in an entertaining way.

- Sacrifice some of the revenue stream from voting to create a system that isn't as vulnerable to manipulation (people need to believe that their votes are meaningful if they're going to keep paying attention and spending money to vote).

- Recognize that music trends don't stay the same forever. There was a minor nod in this direction this year as David Cook got more kudos and promotion from the judging crew as the show progressed. The interesting thing about him was that he already sounded like a lot of what's on the radio, and his looks and personality didn't hurt either, so it was easy to imagine him as the winner.

Jason -- CATS is sung by cats?! -- Castro

Most of the material that gets sung on the show is from a time before these kids were born (was it such a big surprise that Jason didn't know that CATS showstopping Memory was sung by an old dying female cat?), so it isn't that surprising that it's more popular with people older than 50 than with teenagers and 20 somethings.

It would help the producers to look at this from a "jobs to be done" perspective, rather than a "what we want to sell" perspective. The job to be done is to engage the youth audience (primary music buyers), identify a new "star" that they relate to, and create records that are current and interesting to that audience. Like Chris Daughtry did (but then, he had the advantage of being voted off and picking his own band and music -- hmmmm.)

Understand that superstar singers and bands sing hit songs. After spending most of the season telling contestants that song selection is critical, how much sense does it make to give your winner songs which don't fit their style (make a blues guy sing a sugary pop song, for example), or which are simply crap (letting amateur song writers write stuff that is total trash musically and lyrically) and then asking a newly minted winner to make it a hit song is absolutely nuts.

One possible voting system that could work better would be to count song downloads from iTunes in the 24 hours following the performance show. Even if it cost the same as texting in a vote, the fact that you get the song with it would be a big discouragement to VFTW, and iTunes doesn't let you buy the same song twice (at least not easily).

These are some easy big things that would make things more authentic, freshen things up, and introduce some sustaining innovations to counter the disruption to American Idol's artful guise. There are several smaller things as well, but the above would be a healthy start. If not, watch for even bigger declines next year, and a franchise that may not recover from disruption.

The Disruption of American Idol

Disclaimer: This article is not about disruptive innovation per se, but is more of an entertaining diversion into a different kind of disruption. It does, however, have analogs with the kind of disruption we normally like to explore here, so for fun, I use a similar analytical framework.

Ok, I'll admit it. I too have guilty pleasures. American Idol is one of them.

Back when AI first began, I studiously ignored it. My wife got hooked by the third or fourth show, but I thought the whole idea was dumb and never bothered.

The first show I sat through was the finale of the first season, which I thought was pretty pathetic. I hated both singers. They were too amateurish, and although Kelly Clarkson was clearly better, that was only because her competitor was soooooo bad.

Then came the second season. My suspicions confirmed by the first season finale, I ignored the first 5 or 6 weeks

Then for some inexplicable reason, probably boredom, I sat through a show because my wife was watching it. Then I got hooked.

It was still like watching a train wreck happen for many of the below average contestants who couldn't sing in tune or remember their words, but the Ruben - Clay thing was kind of interesting, and I enjoyed seeing the bad singers get voted off one by one. I think that was about when AI started to become the ratings juggernaut and pop star-making phenomenon that it is now.

So, I haven't watched every show since then (not a total addict), but I have come to anticipate my regular fix.

Becoming "The Establishment"

Over the past several years, American Idol has grown in strength, kicking the butt of every show that dares to go against it. America got more and more hooked. Viewership for some regular season shows now approaches Superbowl ratings, and the finale has become so big that it completely encapsulates pop culture

Prince's appearance on last year's finale confirmed the acceptance of AI as part of the establishment and TV royalty. Other than the Superbowl and Y2K New Year's Eve party, what other shows has Prince participated in in recent memory?

Pop stars line up to release new songs or new albums or rejunvenate dead careers on the show. Other TV shows covet the spots before and after AI's time slot, and all FOX has to do to create a new hit is let it follow AI for a few days.

New movies are released by offering boondoggles for Idol participants. Actors with new movies out show up in the audience just to be seen. And, they'll pay anything just to secure a seat in the studio audience if they haven't got something to promote.

The Today Show, the leading morning Infotainment program routinely reports the previous night's Idol results as one of the top three lead news items of the day -- results from a competing network's "reality" show! Virtually every major media outlet now announces the American Idol results on a weekly basis.

Yes, American Idol rules the roost, but trouble is on the horizon.

The Sweet Sound of Disruption

Melinda Doolittle: Is She the Best American Idol Singer Ever?

So, with all the money and star power and publicity and seemingly ever-increasing ratings, how can I say that American Idol is being disrupted? Simple -- the best pure singer the show has ever had, with a voice equal to any pops-topper of the past 40 years, was voted off last week. Amazing!

How could this happen?

Why I Might Be Wrong

Before I delve into the analysis demonstrating that disruption is indeed happening, let me first explore why others might say that I'm wrong.

Many will say that the voters are always right. If the two left are the ones who collected the most votes, then they must be the best, or the most exciting, or have attracted the best following. Especially with over 60M votes being cast -- more than the totals for any presidential election ever.

But realistically, is that possible? Or more to the point, why did Sanjaya last so long?

Why Did Sanjaya Last So Long

An unholy alliance, perhaps? The crying little girls were part of it, and so was the Indian demographic. So was a group who truly found him entertaining and refreshing and thought he as a good singer.

But the influence that tipped the balance could only have come from a blog which encouraged its readers to all get behind the very worst performer left and try to keep them alive week after week.

Vote For the Worst

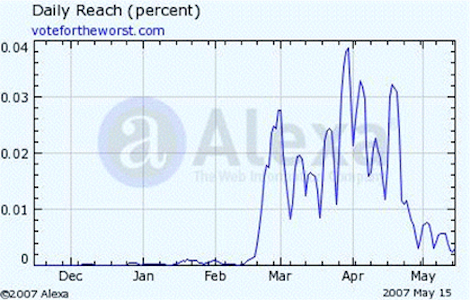

This graph of website reach statistics from Alexa shows the impact that votefortheworst.com has had during the 2007 season of American Idol.

Readership starts to rise just as the public voting season gets underway in mid-February. Spikes correspond to the Monday to Wednesday period each week. The site's heaviest draw was during the period of mid-March to mid-April when Sanjaya seemed to defy gravity and the odds week and week, until his final performance of Bonnie Raitt's "Something to Talk About" which was so dismal, even the tinniest of adoring teenage girls' ears could detect the poor quality of performance.

The biggest peak almost hits .04 percent of all internet traffic for a single day near the end of March, which is far above the average reach estimated by Alexa of .0475 percent of global internet traffic in a week. Using Nielsen data to estimate visitors, this reach equates to approximately 2 to 3 million US-based readers in an average week.

If we can safely assume that at least this many votes were influenced to "vote for the worst" (who this site identified as Sanjaya), it's more than enough in a close contest to keep an individual competitor in.

Vote for the Worst was a little subversive blog site that started in 2004. Having all the right qualities to grow with viral explosiveness, it now has a readership that at its peak this season averaged 500,000 hits per day (coincidentally, that peak occurred in the period when Sanjaya seemed to be invincible, and the media started questioning why such a bad singer was able to survive week after week, while better singers were being voted off.

The Alexa "Daily Reach" graph (shown right) clearly indicates that votefortheworst.com had the intended affect, and was responsible for ensuring that Sanjaya survived for several weeks past when he should have.

VFTW succeeded in having their good fun, and with the vote distributed between lots of candidates and those near the bottom being particularly vulnerable, a small boost in vote is plenty to alter the result and keep the weakest contender alive.

But, What About Melinda

That's a very plausible, reasonable and highly probable explanation for the survival of Sanjaya, but how does it explain the ouster of Melinda, clearly the best and a strong judges' favorite

As the vote totals rise, and the number of finalists goes down, shouldn't that increasingly favor the best? Moreover, what proof do I have that the vote was close?

DialIdol's busy signal statistics show that last week's semifinal was extremely close with all three contestants having almost identical busy signal percentages on their voting lines. When the voting is this close, the margin of error is bigger than the difference between the contestant's votes, making a reliable prediction nearly impossible.

With over 60 million votes cast, and statistically insignificant differences separating first place voting from third, a very small number of votes can make a huge difference, as we saw in the 2000 presidential election where subjective decisions about every hanging chad dictated the outcome. The Alexa graph above shows that fewer people are visiting votefortheworst.com now than when Sanjaya was still alive, but they are still influencing over 1 million votes per week.

VFTW is now supporting Blake as the worst remaining singer. However, like Sanjaya, Blake also has a strong fan base to count on. As the only (somewhat attractive) male left, he draws the majority of the teenage and younger female votes. He is also perceived to be more up-to-date in his musical styling, and more of an "interesting performer" with better stage presence than either of the women.

The extra information we need comes from DialIdol.com.

DialIdol provides software which enables avid voters to speed dial their Idol votes from their computers. In addition to helping fanatical young voters get the maximum number of votes recorded for their choice in the allotted time, DialIdol also records how often a busy signal is obtained when trying to vote.

As we might expect, there is a high correlation between frequency of busy signal and the respective singer's rank in the results show (i.e. the more often the voting number is busy, the more people are trying to cast votes for that singer.)

DialIdol uses this data to publish predictions of the most likely winner and loser each week. (It's hard to believe we're so obsessed with this that we can't wait a few more hours for the actual results show, but there you have it.)

Close Voting Favors the Disruptor

In the week that Sanjaya was voted off, DialIdol accurately predicted the bottom three, including that Sanjaya would be loser. In all preceeding weeks, he was safely in the middle. Last week, as the "DialIdol Rank Graph" below indicates, the voting was too close to predict vote ranking for anyone. So, either the audience didnt agree with the unanimous assessment of the judges and most observers that Melinda knocked it out of the park, or something was helping the poorest singer to stay alive.

Impact of AI Disruption

FOX network at first denied that VFTW was having any impact. Then, when it was clear that they were having an impact, FOX called them "hateful" and "mean-spirited". Ironic accusations from the show that deliberately calls out the most delusional and sometimes mentally-challenged entrants to callously make fun of them in the beginning-of-season reject shows.

But mean-spiritedness is surely what the FOX execs feel who rightly understand that the long-term health of the franchise is at stake, and that the sham that American Idol built upon is being exposed and therefore the business model threatened.

What sham?

American Idol is positioned as a contest to find the best undiscovered young (amateur) singer in America, thereby "discovering" them and making them into a star. But that basic idea is a lie. The audition process is not designed to find the best singers, but the best contestants for a reality show.

Of course, the producers want a decent singer to win at the end, so they put "judges" in place to try to guide and influence the public voting. In any given year, there are about 3 or 4 who are actually good enough singers to deserve a recording contract, so as long as the show eventually whittles down to 2 or 3 of that group still standing, and generates a built-in fan base and familiarity to sell records the producers have won.

Say it ain't so! The sham: it isn't a real singing competition until we get down to the last 2 or 3.

In the mean time, the show needs to provide entertainment, and a pure singing competition would get awful boring awful fast. Admit it -- we all watch because we like the train-wrecks, because there are crazies who make things funny, because we like to see bad singers insulted by Simon, and we like to see them insult Simon back and then take their medicine by getting voted off.

But, and this is a very important 'but', it isn't a real singing competition until all but the last 2 or 3 have been eliminated.

Here's another way of looking at it. Does anyone really believe that out of more than 100,000 auditions, there are only 4 or 5 people who can carry a tune moderately well?

In the general population, there are at least 2 or 3 per hundred selected at random who can sing well. If those 100,000 were selected randomly, there should be a couple of thousand potential contestants. But they self-select, which means they either believe they have some talent or just want to be on TV, but that still means that the ratio should be more like 4 or 5 out of 100.

But, the audition process skims most of the crowd, looking either for good personalities for the finals, or oddball personalities for the "audition" rounds, which are highly staged for TV. Either way, it is TV presence that matters, not singing ability

After all, out of 15 to 20 thousand people in any given city, only about 10-15 get on TV, and most of those get the TV spot so we can laugh at how bad they are. But the show would have us believe that outside of the few who are picked for Hollywood, everyone else is mediocre or less.

VFTW exposes this sham.

They recognize that American Idol wants train wrecks in the final 12 to keep the show entertaining while we get to know the "real" finalists. Which is why there are so many in the top 12 who can't sing.

VFTW agree that it's funny, so they want to keep the train wrecks on as long as possible, and in the process they are slowly but surely eroding the premise that the show is based on by exposing the lie that it really isn't about finding the best singer. And, they need almost no resources, no money, little time -- just a small blog to undermine the show's foundation.

That's why poor Melinda lost last week. That's a personal slap at her, but it may end up being the straw that broke the camel's back as far as the show is concerned. AI didn't care who she sang against, but everyone wanted the best singer to be in the final.

So, the real cost of disruption is that America starts to realize there is a wizard behind the curtains trying to manipulate them into picking who they always wanted us to pick, and once we realize we've been fooled, we lose interest, they lose their star-making machine and the billions of advertising dollars and promotional opportunities that the show has spawned.

And the outcome may be that VFTW forces a change in process which makes the show more honest but less interesting. That's a real world example of the power of disruption -- either way it costs and it may kill the target if the response to the threat isn't met successfully.

Nobody said that all disruption was good.

Food for Thought

- Could FOX or American Idol's producers have anticipated this?

- How should they have reacted to the disruptive threat?

- Is there anything they could still do to neutralize it before next season?

- How would you know if the crown jewel of your business was about to be disrupted?

- Can you deliberately create disruption like this to upset your competitors (in an ethical and legal way)?

More Conventional Opinions

- http://www.buddytv.com/articles/american-idol/american-idol-was-melindas-eli-6559.aspx

- http://www.tvgasm.com/recaps/american_idol/melinda_what_happened/

- http://www.foxesonidol.com/cgi-bin/ae.pl?mode=1&article=article2119.art&page=1

- http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2007/05/american_idol_lets_get_political.html

- http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2007/05/has_american_idol_jumped_the_s.html

- http://www.cinemablend.com/television/American-Idol-Melinda-Is-Eliminated-4266.html

- http://www.point-spreads.com/content/view/1807/2/